What comes to mind when you hear the phrase regime change? Donald Rumsfeld and Iraq? Or maybe some kind of popular uprising or coup d’état?

That’s the usual understanding: the replacement of one governing body with another. But the regime metaphor can be applied more broadly as well. Not just to political regimes, but also to, say, food and energy regimes.

Imagine that our food and energy regimes are each situated on metaphorical landscapes of all possible regimes – landscapes of possibilities. How might this concept help us understand and enable the transformation of maladaptive regimes?

The regimes-on-a-stability-landscape metaphor underpins writings on both resilience and transition management. And it reflects research in complex adaptive systems. Garry Peterson of the Stockholm Resilience Centre will keynote next month’s International Society for the Systems Sciences (ISSS) conference with a talk on “regime shifts,” and incoming ISSS president David Ing will feature these ideas in his address.

I’m speaking at ISSS as well. In my talk, called “design for social change,” I’ll examine the regime metaphor as a means of understanding, critiquing, and enabling efforts at social transformation. It’s a topic I’ve been discussing with various networks of collaborators, especially Greg Hill and my colleagues at Ecotrust.

In this post I survey relevant background literature and then frame some questions for moving forward.

Background: Fitness landscapes

The landscape metaphor originated in the 1930s, with geneticist Sewall Wright’s studies on biological evolution. Wright imagined the relative fitness of genotypes mapped onto a landscape of peaks and valleys. The question he sought to explore was: What if the current fitness peak is sub-optimal, overall? (1)

Biologist and complexity theorist Stuart Kauffman interprets Wright through “an adaptive walk on a fitness landscape”:

The first essential feature of adaptive walks is that they proceed uphill until a local peak is reached. Like a hilltop in a mountainous area, such a local peak is higher than any point in its immediate vicinity, but may be far lower than the highest peak, the global optimum. (2)

The process of escaping a sub-optimal peak is described by Kauffman’s collaborator, biologist Simon Levin:

Sewell Wright, in his 1931 paper, presented a fundamental mechanism by which populations could escape from local peaks. He argued that a large population will be broken up into smaller populations, distributed over a variety of habitats. The local adaptation of these subpopulations to differing conditions helps maintain a heterogeneity in the population that, through emigration and sexual recombination, generates a much larger range of variants than could mutation alone. Wright argued that this shifting balance theory provides one important mechanism by which variation is maintained and the search for optima is enhanced. (3)

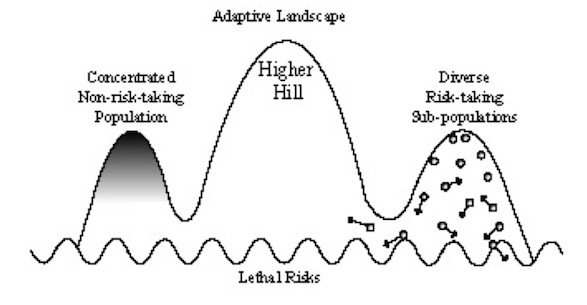

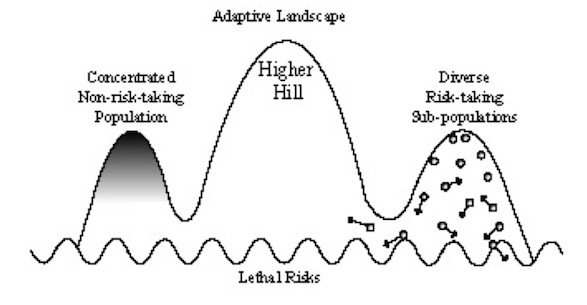

Here’s how economist and mathematician David Ellerman visualizes Wright’s shifting balance theory, showing diverse subpopulations as better able to exploit opportunities on the landscape. (4)

While there are clear distinctions between the fitness (or adaptive) landscape of genotypes and the stability landscape of social-ecological regimes, the earlier metaphor is analogous – and, to my mind, informative – to a discussion of regime change. Here’s why.

Consider Wright’s burning question. He sought to understand the process whereby populations might escape local peaks. Our current challenge is similar: how to break free from maladaptive regimes. Both landscapes illustrate the benefits of diverse and heterogeneous risk-taking – in poplar terms, of innovation. And, both landscapes are continuously evolving, both through extrinsic environmental forces and also through biological and social-ecological interactions. Change happens.

(Note that, while Wright’s work is widely cited in evolutionary biology, his metaphor has also faced criticism.) (5)

Background: Stability landscapes

The stability landscape metaphor can be traced back to the 60s and 70s work of biologists and ecologists Richard Lewontin, Buzz Holling, and others. Contrary to Wright’s landscape of convex peaks, alternative stable states were visualized as concave basins, sometimes called domains of attraction or simply: regimes. (6)

Since then, researchers have developed the stability landscape model and metaphor as a means of understanding ecosystem resilience and transformation. A regime shift occurs when a system crosses a threshold to another basin, like when a clear lake that is over-polluted with fertilizer runoff becomes filled with algae, or grassland that is overgrazed turns to woody shrub land or savannah.

The Stockholm Resilience Centre maintains global databases of such regime shifts and thresholds. Here is a short video describing the concept. (7)

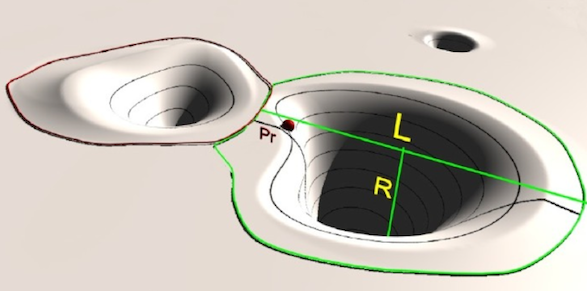

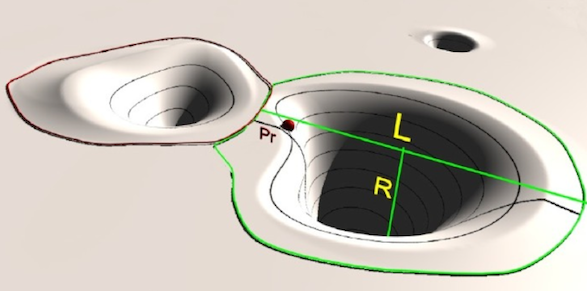

As shown below, regimes can be characterized by: their resistance (R) – their rigidity to change; their latitude (L) – the amount they can be changed without losing their structure, function, and identity; and their precariousness (Pr) – the distance of a social-ecological system to a regime threshold. (8 – figure 1)

Regimes and transformation

Development of a framework for transformation might begin by characterizing today’s landscapes of dominant and alternative (or niche) regimes. In the literature on transition management a regime is defined as “a coherent configuration of technological, institutional, economic, social, cognitive and physical elements and actors with individual goals, values and beliefs.” (9)

Questions that might be considered in such an examination include:

- In what senses are today’s dominant or alternative regimes “coherent configurations”?

- In what senses might regime resistance, latitude, or precariousness differ between, say, dominant food and energy regimes?

- How did these regimes come into existence, at what spatial extents to they operate, and how do they – or might they, in the future – leave individuals, communities, and societies vulnerable?

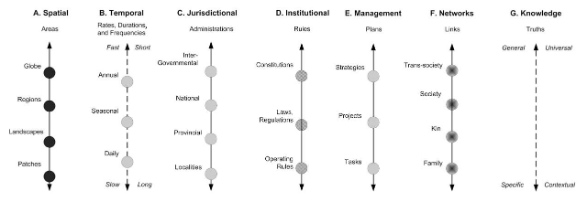

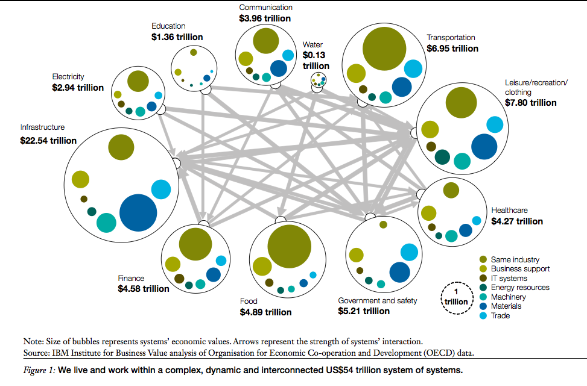

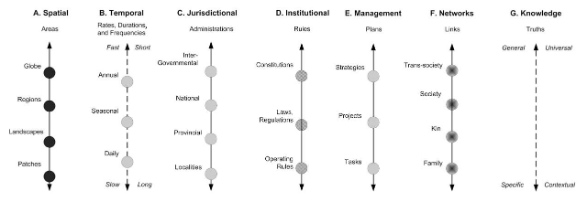

Critical to such system and regime characterizations are assumptions about scales and levels. Here is one approach to definition, taking scale to mean spatial, temporal, quantitative, and analytical dimensions and level to mean units of analysis on each scale. (10 – figure 1)

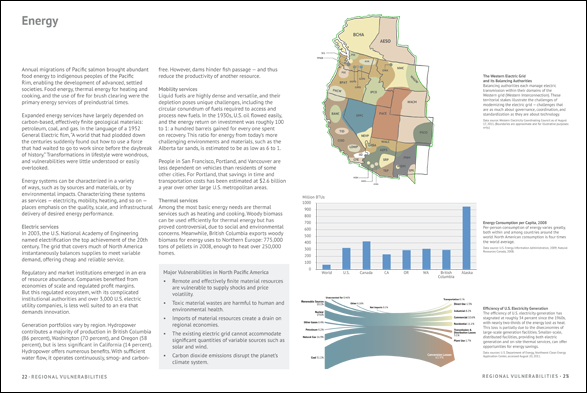

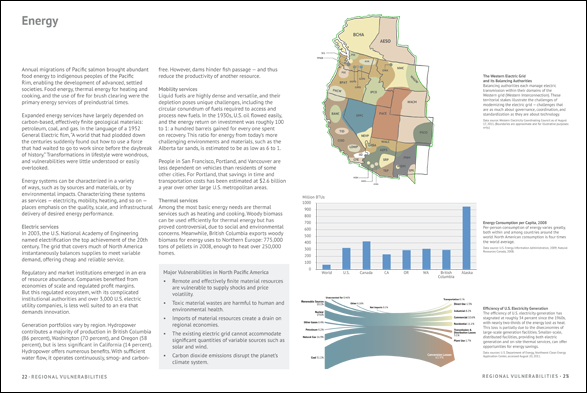

My Ecotrust colleagues and I explored these types of questions in the publication Resilience & Transformation: A Regional Approach (html, pdf, flash-based online viewer). We examined seven regimes of significance to our home region of North Pacific America. Here is an example page spread.

Moving forward

In sum, the regime landscape metaphor offers a systems approach to examining processes of social change.

Here are a few questions I plan to explore in my ISSS talk.

Your thoughts?

Notes

(1) Wright, Sewall. 1932. The Roles of Mutation, Inbreeding, Crossbreeding and Selection in Evolution. Proceedings of the Sixth International Congress of Genetics. http://www.esp.org/books/6th-congress/facsimile/contents/6th-cong-p356-wright.pdf

(2) Kauffman, Stuart. 1995. At Home in the Universe: The Search for the Laws of Self-Organization and Complexity. Oxford University Press. pp.149-189.

(3) Levin, Simon. 1999. Fragile Dominion: Complexity and the Commons. Helix Books / Perseus Publishing. pp.117-156.

(4) Ellerman, David. 2010. Pragmatism versus Economics Ideology in the Post-Socialist Transition. Real-World Economics Review 52:2-27. http://www.paecon.net/PAEReview/issue52/Ellerman52.pdf

(5) See, for example: Reiss, John. 2009. Not by Design: Retiring Darwin’s Watchmaker. University of California Press. pp.176-177. Also Levin, op. cit.

(6) Holling, C. S. 1973. Resilience and Stability of Ecological Systems. Annual Reviews: Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 4:1-23. http://www.iiasa.ac.at/Admin/PUB/Documents/RP-73-003.pdf

(7) Regime Shift video by Kit Hill on Vimeo.

(8) Leuteritz, Thomas E. J. and Hamid R. Ekbia. 2008. Not All Roads Lead to Resilience: A Complex Systems Approach to the Comparative Analysis of Tortoises in Arid Ecosystems. Ecology and Society 13(1). http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol13/iss1/art1/

(9) Holtz, Georg, Marcela Brugnach, and Claudia Pahl-Wostl. 2008. Specifying “Regime” — A Framework for Defining and Describing Regimes in Transition Research. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 75:623-643.

(10) Cash, David W., W. Neil Adger, Fikret Berkes, Po Garden, Louis Lebel, Per Olsson, Lowell Pritchard, and Oran Young. 2006. Scale and Cross-Scale Dynamics: Governance and Information in a Multilevel World. Ecology and Society 11(2):8. http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol11/iss2/art8/

Ecologist

Ecologist