A growing field of research and writing explores the nature of climate change skepticism and denial.

There is the Six Americas study of ways in which Americans engage with the issue. There are a variety of research programs related to the Cultural Theory typology of people as having hierarchist, individualist, egalitarian, and fatalist tendencies. And there are surveys of cognitive and behavioral challenges to climate change perceptions, like the one developed by Kari Marie Norgaard. I wrote about each of these topics and more at P&P.

“Let’s bring together people with divergent views on climate change,” announced the Climate Change Open Forum website. The forum happened last weekend in Portland, with a series of discussions around the city. I spoke briefly at the Saturday evening session, which succeeded in attracting a sizable, diverse audience.

In preparing for my talk, I thought about the common labels for climate action contrarians: skeptic and denier. I wanted to explore my own areas of skepticism and denial. After all, one can recognize the strength of the core science — like the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Working Group I research on observation and attribution — and still hold a variety of feelings on climate change.

So I asked myself: In what ways am I skeptical? What are my own denials and what denials do I encounter in others?

This seems to me like a valuable exercise, and at the beginning of my talk I encouraged everyone in the audience to engage in his or her own critical reflection. With more time, I would design this type of session to allow for break-out discussions and full-group harvest on these questions.

In my experience with these types of conversations, the denials that often come up are the ones related to personal habits. Am I doing enough in the way I live my life? For example and for myself, I ride my bike most days, but I still eat meat.

In the charged atmosphere of the Open Forum, and without the opportunity to each explore our own denials, the sense of denial surfaced as an accusation of hypocrisy. An audience participant pointed out that numerous folks urging climate action had flown into town for the event. Implications of denial can easily open Pandora’s box.

To get beyond the area of individual habits, think of the question about denial as a fill-in-the-blank exercise, one that goes like this: “We are in denial if we think that __________.”

Here are a couple that come to mind for me:

- We are in denial if we think that research in the natural sciences can ever prescribe a clear plan of global climate action.

- We are in denial if we think that there will be solutions to climate change, in any usual sense of that word.

Skepticism is a very different from denial. Skepticism is crucial to good science and a perspective for evaluating potential policy or other engagements. And, just as importantly, it’s a perspective for designing engagements as experiments — that is, as opportunities for learning and adaptation.

On the climate issue, if you dig into some of the most outspoken skepticism about the claims of climate scientists, often what you’ll find underneath is skepticism about potential policies. Nothing surprising about that. We are all vulnerable to such fact-value entanglements, even if some scientists are able to maintain a purely professional stance.

The trick is to not let skepticism become an impediment to action. Quite the contrary, as I noted, skepticism is critical to effective action.

Here are a few examples of my own skepticism:

- Although the Earth’s atmosphere is a global commons, I am skeptical that deliberations about mitigation necessarily need to take place at a global level. It may be that today’s most significant conversations take place within cultural and physical contexts, where appropriate needs and inter-personal understandings are better negotiated.

- I am skeptical that any global mechanism for ratcheting down emissions — even the best conceived ones, like the Greenhouse Development Rights framework — would function entirely as intended.

- I am skeptical that any combination of primary energy sources — like sun and wind and geothermal — will ever be able to truly substitute for the energy supplied by energy-dense fossil fuels.

- I am skeptical that we can comprehend what it feels like to be caught in the maelstrom of a major evolution of worldviews or paradigms, which seems to be what is happening.

These are my acknowledgements of skepticism and denial.

Your turn. What are you skeptical or in denial about?

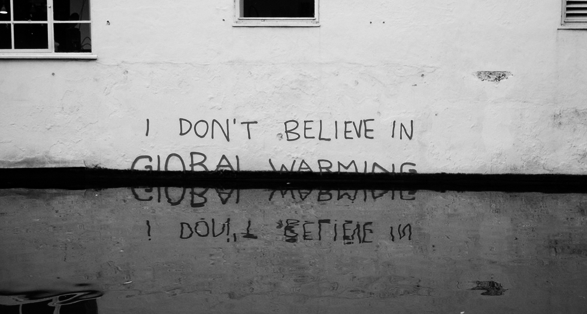

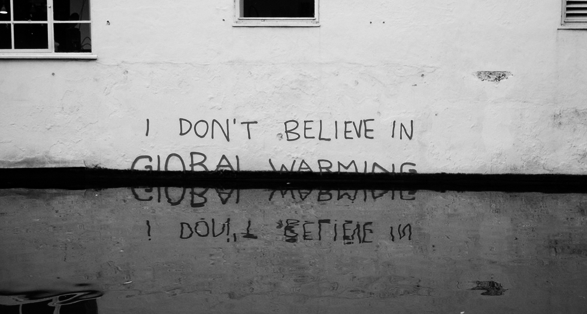

Photo: graffiti attributed to Banksy at Regent’s canal, north London, from a photo by Mangus D