Numerous climate commentators — from economist Nicholas Stern, to social psychologist Nick Pidgeon and communications researcher Matthew Nisbet — have emphasized a risk-based understanding of the climate challenge.

Numerous climate commentators — from economist Nicholas Stern, to social psychologist Nick Pidgeon and communications researcher Matthew Nisbet — have emphasized a risk-based understanding of the climate challenge.

This year, a couple of intriguing new climate initiatives take risk-based approaches. One is the global C40 Cities Climate Risk Assessment Network, which aims to develop a C40 Risk Assessment Framework for use by municipalities around the world. Another is the Risky Business project, pictured above, which, carrying the imprimatur of co-chairs New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg, former U.S. Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson, and Farallon Capital founder Tom Steyer, aims to assess U.S. financial risks and engage leaders in key sectors.

More power to them. Still, if we step back and ask — What is this thing called “risk”? — it turns out to be a tricky question.

A glance around my bookshelf reveals numerous perspectives: the landmark toxicology study Generations at Risk: Reproductive Health and the Environment, the cultural theory of risk perception described by Mary Douglas and Aaron Wildavsky, the modernity-as-risk theorized by Ulrich Beck, the analytical-deliberative approach to risk-informed public processes recommended by the U.S. National Research Council, odds-making on humanity’s future by Martin Rees, and so on.

In the terminology of Knightian uncertainty, coined in 1921 by economist Frank Knight, risk is distinguished from uncertainty. Knight defined risk as “measurable uncertainty” — in situations where one can calculate the odds of various potential outcomes.

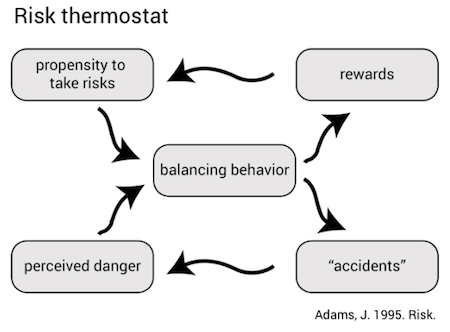

The 1995 book Risk by John Adams took a phenomenological approach to the Knightian distinction. Call it: amidst uncertainty, perceiving risk. Uncertainty is what’s inescapably out there. Risk is how we account for it. Adams:

The development of our expertise in coping with uncertainty begins in infancy. The trial and error processes by which we first learn to crawl, and then walk and talk, involve decision-making in the face of uncertainty. In our development to maturity we progressively refine our risk-taking skills; we learn how to handle sharp things and hot things, how to ride a bicycle and cross the street, how to communicate our needs and wants, how to read the moods of others, how to stay out of trouble. How to stay out of trouble? This is one skill we never master completely. It appears to be a skill that we do not want to master completely.

He calls his model “the risk thermostat”:

The model postulates that:

- Everyone has a propensity to take risks;

- This propensity varies from one individual to another;

- This propensity is influenced by the potential rewards of risk-taking;

- Perceptions of risk are influenced by experience of accident losses — one’s own and others’;

- Individual risk-taking decisions represent a balancing act in which perceptions of risk are weighed against propensity to take risk;

- Accident losses are, by definition, a consequence of taking risks; the more risks an individual takes, the greater, on average, will be both the rewards and losses he or she incurs.

See also:

- Adams’ October 2013 slides on “The Public Perception of Risk“;

- The Communicating Uncertainty panel at last month’s Sackler Colloquium on The Science of Science Communication, which begins with a talk by Baruch Fischhoff at ~4:17:45 of the day 1 livestream video.