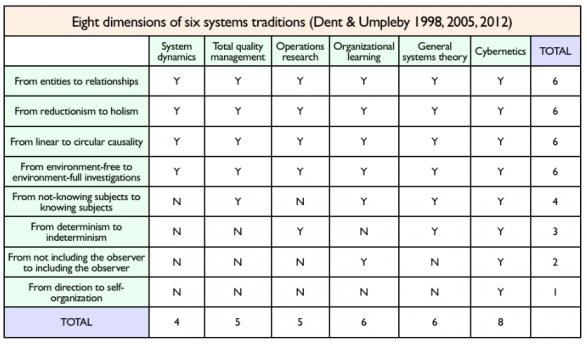

In this comparison of six systems traditions across eight dimensions, I draw from three sources: Stuart Umpleby’s keynote at the 2012 International Society for the Systems Sciences conference, a video of Eric Dent’s presentation at the 2005 American Society for Cybernetics conference, and the original 1998 Dent and Umpleby paper (pdf).

In this comparison of six systems traditions across eight dimensions, I draw from three sources: Stuart Umpleby’s keynote at the 2012 International Society for the Systems Sciences conference, a video of Eric Dent’s presentation at the 2005 American Society for Cybernetics conference, and the original 1998 Dent and Umpleby paper (pdf).

The authors characterize the systems field according to a set of eight dimensions, and then evaluate each of six systems traditions for the presence of each of the dimensions, according to a reading of one book selected as representative for each of the traditions.

The six books are:

- System dynamics — The Electronic Oracle: Computer Models and Social Decisions (1985) by Donella Meadows and J. M. Robinson

- Total quality management — Fourth Generation Management (1994) by Brian Joiner

- Operations research — Handbook of Systems Analysis (1985) edited by Hugh Miser, Jr. and Edward Quade

- Organizational learning — Organizational Learning II: Theory, Method, and Practice (1996) by Chris Argyris and Donald Schon

- General systems theory — General System Theory: Foundations, Development, Applications (1969) by Ludwig Von Bertalanffy

- Cybernetics — The Tree of Knowledge: The Biological Roots of Human Understanding (1987) by Humberto Maturana and Francisco Varela

For concision and clarity, I follow the dimensional labels presented by Umpleby (2012), and I follow Umpleby in using “dimensions,” whereas Dent (2005) calls them “philosophical assumptions.” Here’s how Dent & Umpleby (1998) further describe each of them:

- From entities to relationships — the unit of analysis should be relationships rather than entities

- From reductionism to holism — an entity can be best understood by considering it in its entirety

- From linear to circular causality — cause and effect run both directions and cannot be discretely disentangled (Dent 2005)

- From environment-free to environment-full investigations — the environment plays a role in the manifestation of the phenomenon

- From not-knowing subjects to knowing subjects (reflexivity) — the system of interest is composed of knowing subjects that are able to generate new states in themselves (think new thoughts, do new things) that they never manifested before

- From determinism to indeterminism — at times it is “inherently impossible to determine in advance which direction change will take” (Prigogine & Stengers 1984)

- From not including the observer to including the observer — attention is paid to subjectivity and to including the observer within the domain of descriptions

- From direction to self-organization — “the characteristic structural and behavioral patterns in a complex system are primarily a result of the interactions among the system parts” (Clemson 1984)

Note that Dent (2005) describes each pair of eight dimensions or assumptions as a polarity (“a pair of interdependent opposites”) rather than an either/or dualism. Note also that I follow the yes/no evaluation presented by Dent (2005), which differs slightly from the others.

Thought-provoking work, I’d say — and I’m not the only one, as Stuart Umpleby remarks in the video below.

Some ways to examine it: Are the books truly representative? Do the six traditions offer apples-to-apples comparisons? (In Ray Ison’s recent book, for example, he distinguishes “lineages” like general systems theory from “approaches” like system dynamics.) How about the dimensions or assumptions? Isn’t, say, self-organization an observable phenomenon rather than a philosophical assumption? (In complexity science, self-organization is often listed along with observable phenomena such as non-linearity, feedback, networks, and hierarchy.)

Here is the 2005 video, the first of a three-part talk:

Seems a lot of fuss about little. Let me use the 8 dimensions to explore the normal thinking of engineers, software and enterprise architects (ESEAs). I have shuffled the order for ease of discussion. The first five seem such common sense they barely merit attention.

1) “From entities to relationships — the unit of analysis should be relationships rather than entities.” Naturally, an ESEA could never design a system without defining the relationship between components. However, they cannot generally place one unit of analysis above the other, since they are inseparable and interdependent in the operation of the system.

2) “From reductionism to holism — an entity can be best understood by considering it in its entirety.” Naturally, an ESEA could never design a system without first and last taking a holistic view of it.

3) “From linear to circular causality — cause and effect run both directions and cannot be discretely disentangled (Dent 2005)” Naturally, an ESEA could never build a system to send an invoice (intending to cause payment) without considering the variety of payment/non-payment responses, and the effects they cause on future system behaviour.

4) “From environment-free to environment-full investigations — the environment plays a role in the manifestation of the phenomenon” Naturally, an ESEA can’t design anything (car, photocopier, mobile phone app) without taking into account its use in the environment it will work.

5) “From not including the observer to including the observer — attention is paid to subjectivity and to including the observer within the domain of descriptions.” Naturally, an ESEA cannot design a system that includes human components without including participants and other stakeholders in the process of analysis and design; should capture subjective views etc.

It is not clear to me the next two dimensions make sense.

6) “From determinism to indeterminism — at times it is “inherently impossible to determine in advance which direction change will take” (Prigogine & Stengers 1984)” Does the scale make sense? Non-linear dynamical systems are both deterministic and unpredictable. A weather forecasting system that is perfectly deterministic at the level of designed process will nevertheless produce forecasts that cannot be determined in advance. And despite the table above, the non-linear behaviour of systems may be investigated using system dynamics?

7) “From direction to self-organization — “the characteristic structural and behavioral patterns in a complex system are primarily a result of the interactions among the system parts” (Clemson 1984)” Again, I am not sure this makes sense as written. It seems obvious that structural and behavioural patterns – even in the simplest systems – result from the interactions between systems’ parts. There may be a presumption here that human systems are always more complex than (say) software systems, but that is not true. There may be a presumption that human participants will reorganise the system given to them. Isn’t that really the same point as the last below?

As far as I can see, all this comes down in the end is the fact that ESEAs rarely design a system on the basis that components are self-aware and will change the designed system given to them.

8) “From not-knowing subjects to knowing subjects (reflexivity) — the system of interest is composed of knowing subjects that are able to generate new states in themselves (think new thoughts, do new things) that they never manifested before.”

In such cases, the ESEA may work in partnership with some kind of business change consultant who specialises in the humanities of system change?

Graham, thanks for taking the time to write such a comprehensive response.

Your experience has been vastly different from mine. What you describe as “normal thinking of engineers, software and enterprise architects (ESEAs)” has been the exception, not the rule in my career. In fact, in my own training as a computer scientist and my early work in software development with IBM we were steeped in what I call the traditional worldview (TWV) assumptions – reductionism, linear causality, etc. I’ve then spent the last 25+ years consulting, largely with organizations in the technology world.

I did publish one paper that gives you some flavor of what I found in working with technologists. Although, in this paper I don’t use the terminology of systems science, you will see that there are some humorous examples of what happened when people didn’t fully account for context.

“Technology Clients and Psychology: The Case of Smart Cards,” OD Practioner. (1999). 31 (1), pps. 20-26.

http://faculty.uncfsu.edu/edent/tman633/smartcard.htm

Cheers.

Eric

Dear Graham, Thank you for your long comment. It reminds me of a remark I once heard from Russell Ackoff. He had cited an article as an important contribution. Someone in the audience said, “That is not new. Everyone knows that.” Ackoff insisted that the idea had not been known before (in the academic literature).

As a second example, when I was a graduate student I found that some of my fellow graduate students would read an article and then ask themselves if the conclusions were predictable from common sense. If yes, then the article was not of interest. If no, then it was an important article. I thought that method was the wrong way to evaluate a scientific contribution.

Scientific contributions should be evaluated not relative to “common sense” but rather in relation to previous scientific articles, for several reasons:

1. People disagree on what “common sense” is.

2. Common sense, or what J.K. Galbraith called the “conventional wisdom,” changes in time.

3. Common sense is not precisely formulated.

Hence, common sense does not provide a stable reference frame for evaluating progress in scientific thinking. The academic literature does better.

Eric Dent’s assumptions/ dimensions are even more tricky because authors do not explicitly state them. One reads an author’s work and then asks, is he assuming A or B? Since the assumption is usually not clearly stated, different readers may disagree. Nevertheless, we can state with some confidence that people trained in engineering tend to think one way and psychologists think somewhat differently. What are the different assumptions they are using?

I think Eric’s great contribution is that he pointed out that science expanded in the years after World War II. The range of ideas, or patterns of thought, that scientists dealt with explicitly became larger. Not all sciences have made the transition to this larger world of systems science. In this article (http://www.gwu.edu/~umpleby/recent_papers/2010%20AOM%2012418%20Reflexivity%20Umpleby%20document%202.doc) I note that economists, at least when writing in economics journals, are preoccupied with linear reasoning. However, when journalists described the financial crisis, they used circular reasoning.

I certainly agree that getting agreement on how other people are thinking can be difficult, but Eric has shown that it can be a fruitful exercise.

Only 8 dimensions?

Hi Geoff, what other dimensions for comparing these traditions come to mind for you?

Hi Howard,

from stability (2nd law of thermodynamics) to emergence?

from reductionism to emergence?

from problem definition to problem structuring?

Geoff

I certainly agree that additional shades of meaning might be revealed with additional dimensions. On the other hand, one might argue, for example, that “from stability (2nd law of thermodynamics) to emergence” is described (or implied) already in “from determinism to indeterminism.” No?

I note that Fritjof Capra, who has often relied on this type of “from x to y” characterization of systems thinking, writes in his 2014 book (with Pier Luigi Luisi): “In fact, all these shifts of perspective are really just different ways of saying the same thing.” (p.79)