Last time, I referenced a paper on West Hawai‘i fisheries co-management by Washington State University marine biologist Brian Tissot and coauthors. It’s a story I’m familiar with from interviews I did with Brian and others for the 2012 Ecotrust publication, “Resilience & Transformation: A Regional Approach.”

From that piece (see p.31):

“The West Hawaii Fisheries Council is the best thing that ever happened to fisheries management in Hawai‘i,” declares Tina Owens of the Lost Fish Coalition. “Honolulu retains final authority — but we do all the legwork to reach agreements and make sure the policies work for us.”

This relationship between Honolulu’s Department of Aquatic Resources and the council on the island of Hawai‘i is a notable example of collaborative management of public resources. Co-management relationships can be characterized as ongoing processes of testing and revising institutional arrangements and ecological knowledge. The West Hawaii Fisheries Council emerged from a local process that succeeded in designating over 30 percent of coastal waters as off-limits to aquarium collection. Ten years later, abundance of aquarium species is up and the industry is thriving, with more collectors catching more fish.

More recently, I noticed that this story has also been described through the integral quadrants framework — by Brian Tissot in a 2005 World Futures article that is reprinted in the 2009 book, Integral Ecology: Uniting Multiple Perspectives on the Natural World (of which, a balanced review here).

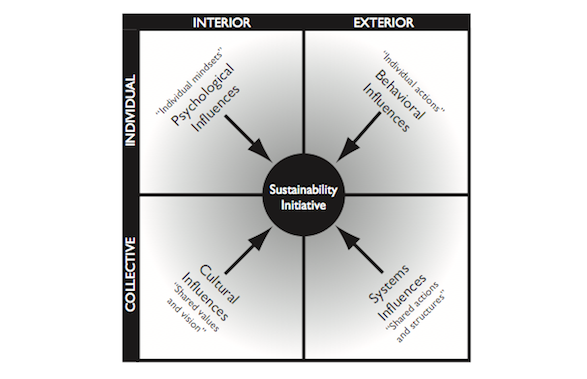

The integral matrix is one of many frameworks I discuss with students in my systems thinking class. It’s basically a 2×2 for examining internal and external dimensions of individual and social situations.

Here is one version, redrawn from the article, “Four Quadrants of Sustainability,” by Barrett Brown:

From Brian Tissot’s article, “Integral marine ecology: Community-based fishery management in Hawai‘i”:

Successful fishery management requires that a dynamic balance of disciplines provide a fully integrated approach. I use Integral Ecology to analyze multiple-use conflicts with an ornamental reef-fish fishery in Hawai’i that is community-managed via the implementation of a series of marine protected areas and the creation of an advisory council. This approach illustrates how the joyful experiences of snorkelers resulted in negative interactions with fish collectors and, thereafter, produced social movements, political will, and ecological change. Although conflicts were reduced and sustainability promoted, lack of acknowledgment of differing worldviews, including persistent native Hawaiian cultural beliefs, contributed to continued conflicts.

Figure design by Andrew Fuller