“If you don’t like capitalism and you don’t like socialism… what do you want?” asked Gar Alperovitz and Steve Dubb in a 2012 article (pdf), published by the Democracy Collaborative at the University of Maryland.

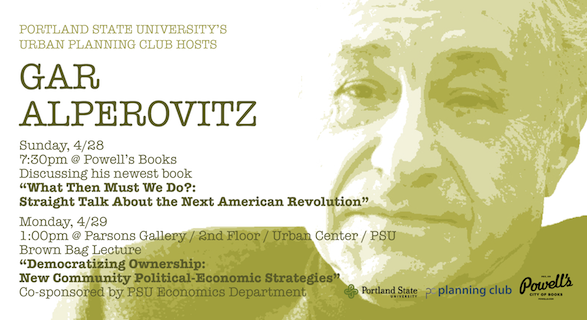

This search for models of social-economic organization that better “build democracy, community and equity” is at the heart of Alperovitz’s forthcoming book, What Then Must We Do?: Straight Talk About the Next American Revolution.

From a February 2013 interview at Solidarity Hall:

In smaller companies, we know that worker ownership is a useful device. Indeed, we are strong supporters of worker coops and worker-owned companies in general. In large firms, worker ownership in some industries might produce different equity results. That is, the larger community has a stake in the impact of their operations. And we’ve been interested in how you can blend these different interests most successfully.

The problem with pure worker ownership of large industries is that the worker/owners are under the same market pressures as any other company. They are therefore as likely to pollute the environment, for example, if they’re under competitive pressures to do so, as the next guys. So that means the worker-owned company’s interests are somewhat different from that of its surrounding community—which includes elderly people, young people, all those who happen to be out of the workforce. After all, half the society at any one time is not part of that worker ownership.

So we think it’s critical, to use economists’ language, to begin to internalize the externalities through structures that reflect the broader community’s interests, rather than putting workers’ interests at odds with them.

From an article last week in Truthout (“The Question of Socialism (and Beyond!) Is About to Open Up in These United States”):

[A] third model that has traditionally had some resonance is to locate primary ownership of significant scale capital in “communities” rather than either the state or specific groups of workers – i.e. in geographic communities and in political structures that are inclusive of all the people in the community. …

Variations on this model include the “municipal socialism” that played so important a role in early 20th century American socialist politics – and is still evident in more than 2,000 municipally owned utilities, a good deal of new municipal land development and many other projects. “Social ecologist” Murray Bookchin gave primary emphasis to a municipal version of the community model in works like Remaking Society: Pathways to a Green Future, and Marxist geographer David Harvey has begun to explore this option as well. (As Harvey emphasizes, any “model” would likely also have to build up higher level supporting structures and could not function successfully were it left to simply float in the free market without some larger supporting system.)

Current suggestive practical developments in this direction include a complex or “mixed” model in Cleveland that involves worker co-ops that are linked together and subordinated to a community-wide, nonprofit structure — and supported by something of a quasi-planning system (directed procurement from hospitals and universities that depend in significant part on public financial support). An earlier model involving joint community and worker ownership was developed by steelworkers in Youngstown, Ohio, in the late 1970s.

See also: Gar Alperovitz’s writing as a set of design principles.