“The creation of Portland Made is a masterstroke,” lauds Oregon Congressman Earl Blumenauer in this video. “You are a key reason why my hometown is truly America’s most livable city.”

Portland Made, which is looking to establish itself as hub-of and brand-for the local designer-retailer-manufacturer movement, is a recent addition to the city’s thriving maker culture. Economist Charles Heying documented the extent of this movement in his 2010 book, Brew to Bikes: Portland’s Artisan Economy, which included a look-back glance at the so-called “200 artisan skills required to make a Victorian town functional.” Heying calculated that Portland makers had maintained or recreated 112 of the skills, nearly two-thirds the total.

To me, this trend is significant for several reasons. One is articulated in, say, Chris Anderson’s thesis of making as the harbinger of a new industrial revolution. Another is resilience — making as part of providing for local-regional needs, as I wrote in this article on jobs of the future.

Still, I think there’s more as well. Consider this question: Is the story of the maker movement just about material goods and functional purposes?

Think analogously. How about school gardens, where children learn to grow vegetables. Is the significance merely about fresh produce for the cafeteria? Or is it also about what’s cultivated in the child? How about Getaround carsharing or airbnb homesharing. Purely functional? Or are there less tangible benefits, a culture of sharing nurtured among participants?

Making, gardening, sharing: What these have in common is that they are practices. As I cited in a post on “the practice turn,” practices are embodiments of agency, expressed in an active voice. Practices are how everyone can contribute to shaping the norms and logics that shape our lives.

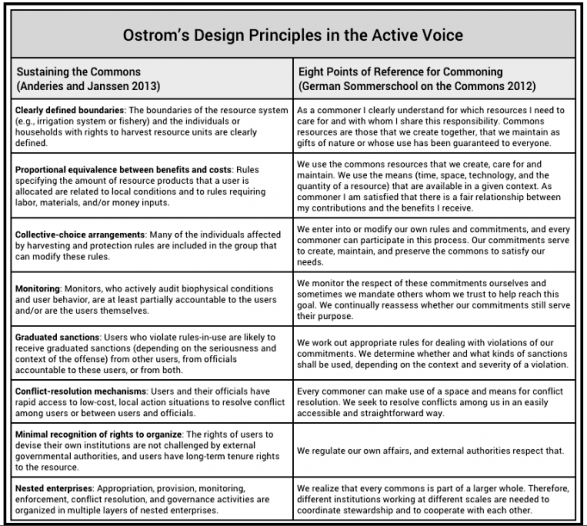

As I was thinking about this stuff, I remembered David Bollier’s description of the 2012 German Sommerschool on the Commons, where participants rewrote Elinor Ostrom’s design principles for management of common-pool resources as practices for commoning (“Eight Points of Reference for Commoning”).

I’ve created a figure with Ostrom’s principles (from the recent book, Sustaining the Commons), side-by-side with the active-voice practices.