A few stories I came across recently have me thinking about the challenges of organizational learning — in this case, with respect to the U.S. military.

A few stories I came across recently have me thinking about the challenges of organizational learning — in this case, with respect to the U.S. military.

“I believe the Army is more interested in learning from its experiences than any organization I had ever been in,” pronounced Margaret Wheatley in a 1997 interview with Scott London.

That’s quite a testament from Wheatley, author of the classic Leadership and the New Science. This exchange came halfway through the interview:

London: You’ve done some work with the Army Chief of Staff and his senior staff. What does the Army have to learn from your ideas?

Wheatley: I had a lot to learn from them. That was one of the interesting things. I went into the Army as foreign territory. It had never been part of my belief system or my politics, actually. What I encountered there, when I was willing to just look around, was a lot of paradoxes.

At the positive end of the paradoxes was the fact that I believe the Army is more interested in learning from its experiences than any organization I had ever been in. Many organizations are now trying to walk under the banner of “The Learning Organization,” realizing that knowledge is our most important product and that that gives us our competitive edge. There is a lot of rhetoric now about how we have to create “learning” from our experience. But the only place that I’ve seen it, though, is in the Army. As one colonel said, “We realized a while ago that it’s better to learn than be dead.” So they had this deep imperative for learning that, certainly at the senior levels, frees them to want to learn from experience and see what they might not want to see.

The Army is an incredibly literate organization. They have internal journals that they use to correspond with one another. They study history carefully. They have a center for Army lessons learned. They document everything. And they have this wonderful process of learning from direct experience called “After Action Review,” in which everyone who was involved sits down and the three questions are: What happened? Why do you think it happened? And what can we learn from it?

If you were in a good American organization and were able to get those three questions as part of your process, you could become a learning organization. What I observe in our business organizations — even in our public institutions — is that after a crisis or breakdown, or after something worked really well, we don’t get together and say, “Okay, what do we each think happened, and what can we learn from it?” We either take credit for it, or, if it’s an error, we try to bury it as fast as we can and move on.

We’re not in cultures which support learning; we’re in cultures that give us the message consistently: “Don’t mess up, don’t make mistakes, don’t make the boss look bad, don’t give us any surprises.” So we’re asking for a kind of predictability, control, respect and compliance that has nothing to do with learning.

So I don’t know how any of these large organizations, both public and private, have a prayer to become a true learning organization, until they move away from these cultures of status and protection and fear of one another. That came real clear to me in the Army.

A key concept here — though Wheatley doesn’t mention it by name — is design. Organizational learning must be designed for — that is, afforded and encouraged through the development of a culture of learning.

A couple of 2010 military publications, the Army Field Manual 5-0 (pdf) and The School of Military Studies Art of Design: Student Text 2.0 (pdf), reflect this design turn.

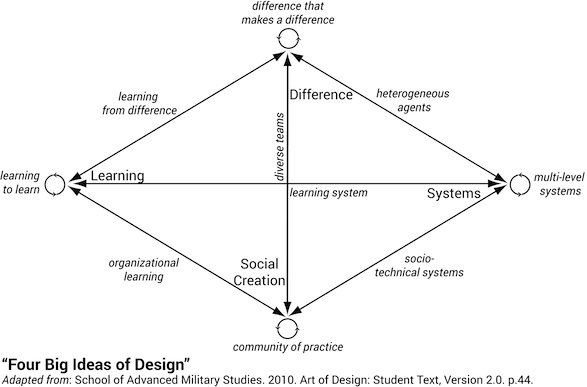

The former offers an informative glimpse into the Army’s operational thinking: “Design is a methodology for applying critical and creative thinking to understand, visualize, and describe complex, ill-structured problems and develop approaches to solve them.” The latter presents a wide-ranging survey of writings on learning, design, systems, and related fields — as, for example, in the figure adapted at top: “the four big ideas of design.”

The story of the Army’s turn to design was recounted by Roger Martin in Design Observer (“Design Thinking Comes to the U.S. Army”), also back in 2010. Martin affirmed that “the Army has gotten design quite right,” while also cautioning that “the struggle to get design well ensconced in Army doctrine was and remains no easy feat.”

No easy feat, indeed — as a report in this week’s On the Media radio/podcast attests. The segment, “Rewriting History,” describes a case in which, against other dynamics, a culture of learning did not prevail in the U.S. military.

It’s challenging stuff — for all organizations — as Meg Wheatley emphasized.