Patterns of social organization and interaction vary from culture to culture, from one social context to another, from one generation to the next. In any particular culture or context, established patterns signal and enforce appropriate action.

Such patterns — i.e., institutional patterns — have been conceptualized in various ways, at various levels of resolution.

One notable approach is called institutional logics. Recently, anthropologist and philosopher Bruno Latour weighed in his own approach, published as both book and augmented website. It’s called An Inquiry into Modes of Existence: An Anthropology of the Moderns.

“The institution is back,” declares Latour. Indeed, institutional analyses, syntheses, re-imaginations, and transpositions are critical to the development of social patterns that better support the flourishing of life.

In this post I’ll introduce logics and modes, while pointing out a couple of comparisons.

Last month at orgtheory.net, sociologist Bayliss Camp offered a personal introduction to institutional logics, reflecting on his experiences in moving between social contexts, from academia to government (“Research outside the academy part II: some background and reflections on institutional logics”):

Finally, I would note that when considering a career in government service, it is useful to think about the implications of the grand logics of different types of organizations (cf. Weber 1922; Dobbin 1994; Meyer and Rowan 1977; Meyer and Scott 1983; DiMaggio and Powell 1991).

We all know, for instance, that those working in for-profit businesses generally judge a given person’s performance through monetary means. It is only more rarely that we reflect on the fact that those working in government agencies tend to judge personal performance through metrics of power. In my experience, it is rarer yet that we admit the truth about academic institutions: that people are judged almost entirely in terms of reputation (and not just one’s own, but more broadly that of one’s advisor as well as one’s institutions, both past and present – see Etzkowitz, Kemelgor and Uzzi 2000).

Switching from one field to another usually necessitates that one be prepared to operate under a different set of institutional rules and expectations. In the case of moving from the academy to the state, this means (among other things) caring much less about what people think about one’s work, and caring much more about making things happen.

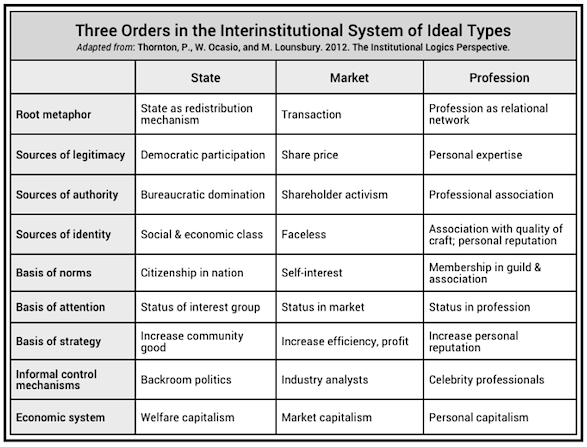

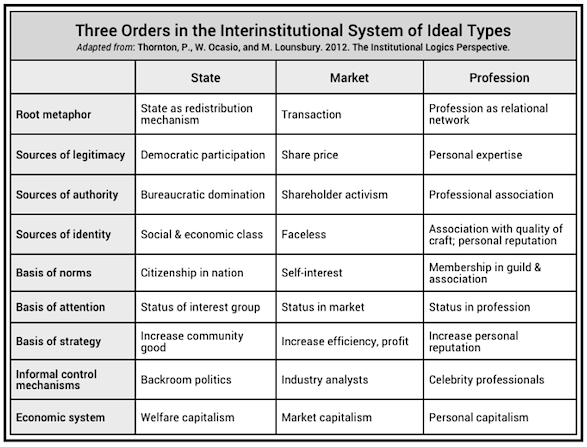

Camp mentions three institutional types — government, business, academy — and describes the norms of performance relevant to each. In the 2012 book, The Institutional Logics Perspective, by Patricia Thornton, William Ocasio, and Michael Lounsbury, these three are called state, market, and profession. (Four others are family, community, religion, and corporation.)

Here’s how Thornton and colleagues characterize them as ideal types:

Ideal types are, well, idealized, and any particular organization or system or “institutional field” might be understood as combining “multiple, fragmented and contested” facets or dimensions from among logical types (Schneiberg and Lounsbury, 2008, pdf).

Ideal types are, well, idealized, and any particular organization or system or “institutional field” might be understood as combining “multiple, fragmented and contested” facets or dimensions from among logical types (Schneiberg and Lounsbury, 2008, pdf).

This, then, is the connection to Latour’s approach. The facets or dimensions from which institutional logics are composed — the meta-logics, one might say — are what Latour calls “modes of existence.”

Latour’s project is to develop a synthetic typology of these modes — “the things that humans concern themselves with — and the questions they ask themselves.” He currently lists fifteen in total: reproduction, metamorphosis, habit, technology, fiction, reference, politics, law, religion, attachment, organization, morality, network, preposition, and double click.

Another distinction between logics and modes is not in the typologies themselves but in the stance of the writers. Logics writings generally take an academic, third-person stance. Latour’s writing (regardless of one’s opinions of it) takes a moral stance — in contemporary lingo, a transdisciplinary or action research stance. He’s directly engaged.

For example, from the modes website:

How do we compose a common world? Not so long ago, the project that would have seen modernization spread over the whole planet came up against unexpected opposition from the planet itself. Should we give up, deny the problem, or grit our teeth and hope for a miracle? Alternatively we could inquire into what this modern project has meant so as to find out how it can be begun again on a new footing.

And from the book:

[W]e shall not cure the Moderns of their attachment to their cherished theme, the modernization front, if we do not offer them an alternate narrative made of the same stuff as the Master Narratives whose era is over — or so some have claimed, perhaps a bit too hastily. We have to fight trouble with trouble, counter a metaphysical machine with a bigger metaphysical machine.

I admire Latour’s commitment.

To be sure, logics writings also focus on organizational and social change. The paper I cited above by Marc Schneiberg and Michael Lounsbury, for example, is called “Social Movements and Institutional Analysis.”

Still, there’s a difference between the passive voice and the active one.

For anyone committed to change, the question becomes: How might I be most effective?

Ideal types are, well, idealized, and any particular organization or system or “institutional field” might be understood as combining “multiple, fragmented and contested” facets or dimensions from among logical types (Schneiberg and Lounsbury, 2008,

Ideal types are, well, idealized, and any particular organization or system or “institutional field” might be understood as combining “multiple, fragmented and contested” facets or dimensions from among logical types (Schneiberg and Lounsbury, 2008,