Last year, resilience pioneer Buzz Holling, one of the originators of adaptive management — an approach to ecosystem management that emphasizes actively testing hypotheses and uncertainties — summarized his experiences in a talk at the American Fisheries Society.

Buzz’ notes on “Lessons from Active Adaptive Management Experience” read to me like a set of design principles or guidelines for engagement with all kinds of issues.

1) In each project, make the overall goal large, and unattainable — things related to justice, equity and opportunity. However, make the first step tough, simple, doable and open. Design the second step from the success and failures of the first and retain the overall, impossible goal. Ditto for each succeeding step.

2) Rarely do organizations experiment, monitor, abandon, and modify. They need to.

3) In any project, the preliminary analysis and communication phase takes one and one half years, with three workshops involving a diverse community. Design several visualizations of past and of alternative futures that can be quickly perceived. Then add one or a few open discussions with people representing combinations of every possible interest. Encourage them to discover stereotypes they have and, from that, begin to communicate across interests.

4) On the side, continue questioning theory, conducting tests and inventing expansions to theory. Your actions change the world, therefore your knowledge is limited.

5) Much of established theory is severely limited at the time — too simplistic, too static, too uniform in scale and perceived by the originators as too certain.

6) The fixed world of standard environmental protection is rigid and wrong. So is command and control. Most management is still command and control.

7) The key failure is of implementation, not of evaluation, or understanding, or policy. That is because the politics of the lobbies freezes abilities to act.

8) So often most environmentalists become narrow “lobbyists”, pushing simplistic explanations , avoiding shared discovery, ignoring uncertainty and hostile to or fearful of adaptive experiments. But that is true of all activist groups. Support them all, but add balance.

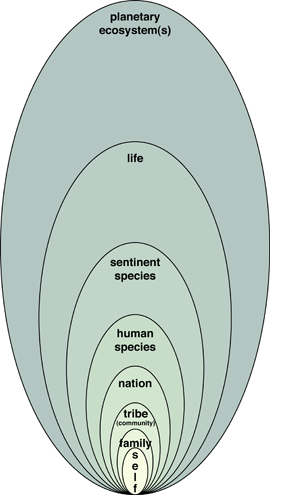

9) We live in a slice of time on a spot in space. Therefore we see myopically. But we adapt if we look across scales, recognize ignorance, monitor and innovate/invent. But lobbies fight that.

10) Organizations begin with brilliance, pause with rigidity and then die or persist with irrelevance. They rarely transform. Therefore, find or invent new institutions and persist in introducing periodic phases of novelty and adventures. The Resilience Alliance is perhaps one such.

11) Beautiful, resilient, flexible policies are never accepted until a social, political window unexpectedly opens; then they can suddenly spread.

12) Design large experiments, with small parts and just sufficient complexity. They will always fail (partly). Learn from the surprises when they fail.

13) Lobbyists oppose experiments to test policies. That opposition usually persists and succeeds in inhibiting change for a good while at least.

14) Resilience comes when individuals can access diversity of opportunity at times of crisis or transformation. Create resilience. Be resilient.

15) Search for and partner with a societal leader who is broadly respected in the region. Often failure of Active Adaptive Management comes at the very end when there is no such effective leader to carry forward the lessons learned into a political arena.

16) Have fun — write limericks, make jokes, invent celebrations, paint and sculpt, dance and make music.

Suggestions on your favorite design principles most welcome.

H/t to Ecotrust, where Buzz’s notes circulated last year.

The

The

I’ve listened to last week’s talks by political economist

I’ve listened to last week’s talks by political economist  “Fellow revolutionaries, I am delighted to be with you,” political ecnomist

“Fellow revolutionaries, I am delighted to be with you,” political ecnomist