“The back loop is the time of the Long Now,” writes Resilience Alliance founder Buzz Holling. It is a time “when each of us must become aware that he or she is a participant.”

“The trick is to treat the last ten thousand years as if it were last week, and the next ten thousand as if it were next week,” advises Stewart Brand in The Clock of the Long Now. “Such tricks confer advantage.”

Though Brand’s book precedes Holling’s “Complex Worlds” paper, their dialog runs pretty much like that. And the discussion turns on a pair of interrelated metaphors: panarchy and pace layering.

Mapping Metaphors

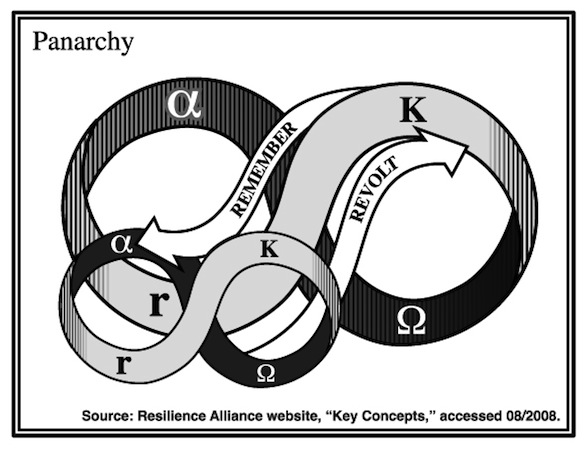

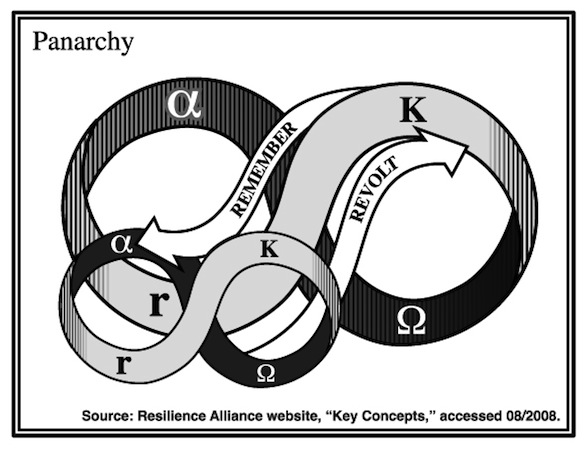

Holling and colleagues represent a familiar pattern of growth, conservation, release and renewal in the model of the adaptive cycle. A layering of adaptive cycles becomes a panarchy. The panarchy represents evolving interactions across ecological and social scales of time and space from, say, the pine cone to the forest to the forest products company.

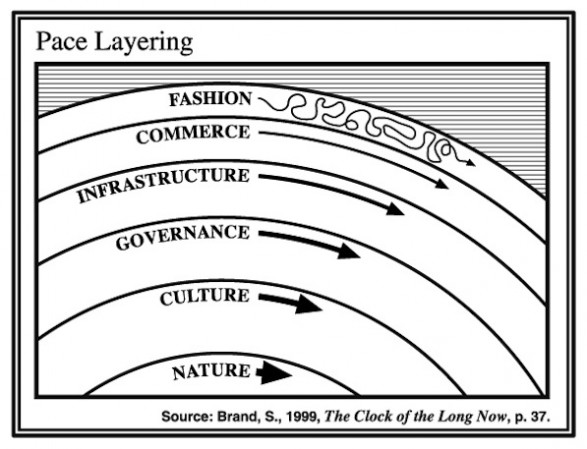

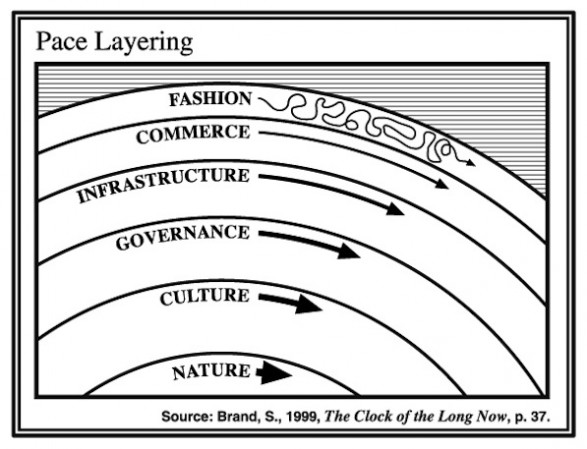

Brand’s metaphor is pace layering, “the working structure of a robust and adaptable civilization.” Organized fast to slow, the layers are: fashion, commerce, infrastructure, governance, culture, and nature. With a nod to Holling, Brand writes, “The combination of fast and slow components makes the system resilient.”

What can we learn by mapping pace against panarchy? Picture a stack of adaptive cycles, with frantic fashion at the bottom, and nature’s biophysical processes, broad and slow, at the top. Reaching from each cyclic layer down to the next is an arrow labeled “remember,” for memory is an important influence that slower cycles exert on faster ones. And stretching from each cycle up to the next is the arrow “revolt,” representing the actions that, in the time of the back loop – of release and subsequent renewal – can enact structural shifts in the cycles above.

These days, the word revolt doesn’t roll off the lips like, say, “innovation.” Yet innovation can be highly disruptive, as Clayton Christensen has described in business books such as The Innovator’s Dilemma: When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail. Deep social innovation will be no less jarring, one would think.

For change agents (“each of us … is a participant”), the pace diagram offers a map of possible points for revolt (innovation). In this reading, the layers describe a framework not unlike that in Donella Meadows’ “Leverage Points: Places to Intervene in a System (pdf).” With layers as leverage points, the slower the layer, the greater the leverage. As an example of leverage seeking, think of Thomas Friedman’s motto: “Change your leaders, not your lightbulbs.”

Open Explorations

I considered ending this post here, but I want to sketch out some thoughts on timely topics, asking how well these maps facilitate our comprehension. A couple of months ago, drawing upon Resilience Alliance writings about the adaptive cycle’s rigidity and poverty traps, I similarly offered a perspective on an energy regimes. Here, I wonder: With the word “crisis” commonly used these days, in what senses is 2009 the time of a big back loop? And what does high-leverage revolt (innovation) look like?

A Big Back Loop

How is movement through a back loop perceived and described? I reflected on this question as I listened to Steven Johnson’s SXSW talk on the newspaper industry – a prime example of breakdown. Here is Johnson.

There are really two worst case scenarios that we’re concerned about right now, and it’s important to distinguish between them. There is panic that newspapers are going to disappear as businesses. And then there’s panic that crucial information is going to disappear with them, that we’re going to suffer as culture because newspapers will no long be able to afford to generate the information we’ve relied on for so many years.

Johnson describes how first technology reporting and then political reporting have pioneered new models of information dissemination, via the Net. In panarchial terms, actors in these two fields of journalism have passed through the release phase of the adaptive cycle and found paths to renewal. In the case of technology reporting, that outcome may have been a given, but not so for political reporting.

Looking at other systems that are thought to have broken down, are there similarly early pioneers to be identified? What does the process of renewal look like?

High-Leverage Revolt (Innovation)

Sitting atop governance, infrastructure and so on, the long, slow layer of culture presents a tempting “intervention point.” How then is revolt on the cultural layer instigated? Here is Dana Meadows on “the mindset or (cultural) paradigm out of which the system arises.”

So how do you change paradigms? Thomas Kuhn, who wrote the seminal book about the great paradigm shifts of science, has a lot to say about that. In a nutshell, you keep pointing at the anomalies and failures in the old paradigm, you come yourself, loudly, with assurance, from the new one, you insert people with the new paradigm in places of public visibility and power. You don’t waste time with reactionaries; rather you work with active change agents and with the vast middle ground of people who are open-minded.

Today, we see a lot of this happening, with challenges to the appropriate roles in our societies for capitalism, democratic governance, and the media.

Another, more tangible, example of high-leverage revolt is Tom Linzey’s work with the Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund, which has assisted rural municipalities in fending off the establishment of unwanted operations by agribusiness corporations. Linzey describes his work as “collective, civil, nonviolent disobedience through municipal lawmaking.” Here is Linzey, from a December 2007 talk at Ecotrust.

We have never had an environmental movement in this country, because real movements drive rights into the constitution or the fundamental frameworks of government. The abolitionists drove the 13th, 14th and 15th amendments into the constitution. The suffragists drove the 19th amendment into the constitution. We have never had an environmental movement that has focused on the rights of nature. What we have is an environmental movement that has been named such but has been focused on a regulatory system, which even when working perfectly, simply explains or delineates the rate of environmental destruction. That is what the regulatory system is about. These are the conclusions that we have come to. And so part of our work, in Pennsylvania and elsewhere, has been about building a new system of jurisprudence, in which ecosystems have legally defensible rights within that system and are not treated as mere property.

Interestingly, Linzey observes that these interventions on the government layer affect the culture layer as well. “The lawmaking process that we engage in with municipalities is not just us in Chambersburg, Pennsylvania sitting down and writing down an ordinance and handing it to people. It’s actually engaging the communities in the lawmaking process. What we find is that when that starts, it actually starts changing the culture of those communities.”

In terms of pace layering, we might say that, according to Linzey’s observations, the layers are not as static as the diagram would seem to indicate. Culture is constituted of and created out of interactions with the other layers. I am reminded again of Brian Walker and colleagues, from the “Handful of Heuristics” paper. “Revolts can occur either because lower-level cycles are synchronized, and thus all enter a back loop at the same time, or because they are tightly interconnected, so that a back-loop transition in one cycle triggers such a transition in the other cycles.”

Thoughts on seeking leverage?

Portland premiere of

Portland premiere of